Performance Mismanagement: How an Unrealistic Goal Fueled VA Scandal

Talesha Reynolds of NBC News and Allison Linn of CNBC contributed to this report.

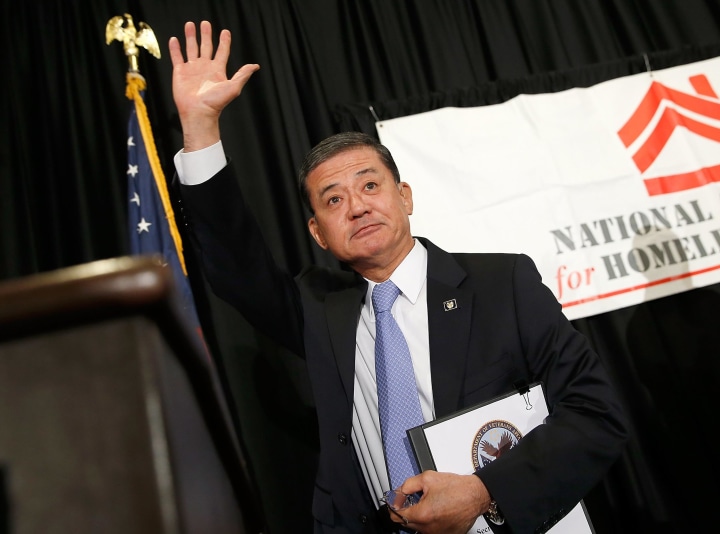

When former Veterans Affairs Secretary Eric Shinseki signed off in 2010 on a plan to attack a massive scheduling backlog by ordering VA doctors to see new patients within 14 days, he unwittingly set in motion a debacle that encouraged cheating and ultimately cost him his job, according to some management experts.

His error, they say, was setting an unreasonable goal.

Many questions remain unanswered amid continuing internal and criminal investigations of “inappropriate scheduling practices” at dozens of medical centers and clinics run by the Department of Veterans Affairs, which whistleblowers allege delayed care for an untold number of military veterans and cost some their lives.

But interviews with experts in performance management, and an examination of VA documents and congressional testimony by NBC News, indicate the agency’s internal controls were woefully inadequate when it came to tracking progress toward the goal approved by Shinseki.

Not only did the system fail to produce accurate and actionable data, but it may have incited front-line VA managers to cheat -- and even rewarded them for doing so, experts say.

“Any time you put highly specific performance measures in place, and you’re reporting them publicly … they become high stakes and it encourages people to do stupid things like gaming the numbers,” said Ellen Rubin, an assistant professor of public administration at the State University of New York at Albany who published a study of government performance appraisal systems in 2011.

Other experts say the experience at the VA mirrors similar failures in the private sector where unrealistic, vague or difficult goals lead to bad behavior, such as car salespeople selling vehicles to people with bad credit to meet untenable sales targets.

“It really is the system that drives this behavior and if you’re going to set up the system, you need to set up also a system of checks and balances,” said Lisa Ordonez, a professor of management and organizations at the University of Arizona.

Such safeguards appear to be largely missing at the VA.

The VA has wrestled with lengthy wait times for more than a decade, and the problem of managers at the busiest VA facilities using creative “gaming strategies” to meet agency targets dates at least to 2008, according to an internal VA memo from 2010.

Win McNamee / Getty Images

Win McNamee / Getty Images

But Shinseki’s approval of the 14-day goal added fuel to the fire, the VA acknowledges. The 14-day goal, since jettisoned by acting VA Secretary Sloan Gibson following Shinseki’s resignation on May 30, “was not attainable given growing demand for services and lack of planning for resource requirements,” the VA said this month in a “fact sheet” on the medical access and wait times.

The goal apparently encouraged managers at busy VA medical facilities to deflate the numbers in reporting patient wait times – practices that the VA’s Office of the Inspector General now says “are systemic” throughout the Veterans Health Administration. The ruses reportedly varied, but were geared toward manipulating data used to determine bonuses and salary increases during managers’ performance reviews.

For example, a preliminary report by the VA’s Office of the Inspector General on May 28 focused on ground zero in the scheduling scandal – the Phoenix medical center -- found that many veterans seeking first appointments there were not entered into the “electronic waiting list” in scheduling software. Instead, according to whistleblower accounts that surfaced in March, paper records widely known as the “secret waiting list” were created, making it appear that the facility was sharply reducing its backlog.

It also found that “certain audit controls” within the scheduling software were not enabled, limiting investigators’ ability to determine whether “malicious manipulation” of the data had occurred.

"Cash awards are seen as an entitlement and have become irrelevant to quality work product."

Congressional investigators say the lack of performance data also contributed to an environment where the awarding of bonuses became nearly automatic.

Rep. Jeff Miller, chairman of the House Committee on Veterans' Affairs, noted during a hearing Friday that the VA paid more than $2.8 million in bonuses to senior executives in fiscal 2013, and that all of the agency’s 470 senior managers received a “fully successful performance review.”

“Instead of using bonuses as an award for outstanding work on behalf of our veterans, cash awards are seen as an entitlement and have become irrelevant to quality work product,” said Miller, R-Fla.

The VA did not respond to a request from NBC News for comment on its performance management system. In a previous response, the agency said, “The 14-day wait time target is a small portion of an individual executive’s performance assessment, which is comprised of nearly 80 separate dimensions of leadership.”

Outside consultant hired

Adding another layer of complexity in Phoenix was the hiring of an outside consultant, Franklin Covey, to provide additional performance training for Phoenix VA employees.

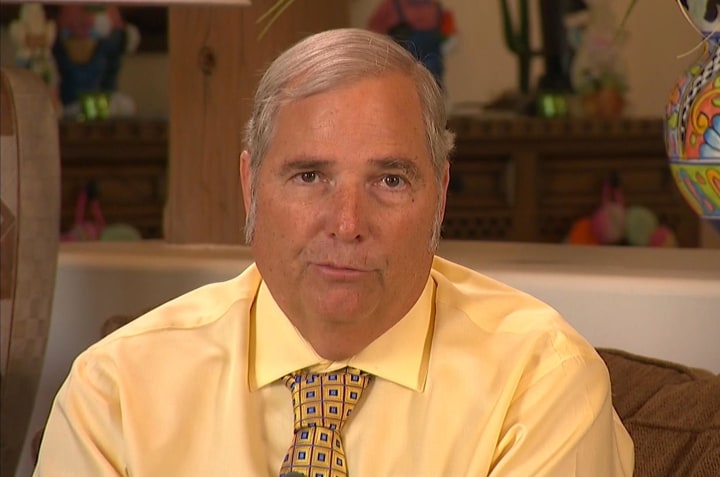

The Salt Lake City-based company conducted a 1½-day session for more than 200 doctors and nurses in Phoenix in late 2012, according to Dr. Sam Foote, a retired VA medical practitioner and one of two whistleblowers who reported scheduling fakery at the medical center. He said that managers at the hospital used a “scoreboard” recommended by Franklin Covey to track progress on the wait time goal.

NBC News

NBC News

Foote called the session with the consultant “ridiculous,” saying that a number of employees walked out when the trainers showed a videotape of a teenager dancing at a rock concert to demonstrate leadership and then “wanted us all to get up and dance around the room.”

He also called it a waste of valuable agency resources.

“They made us go downtown when we needed all the time we could use to work,” Foote said. “… It was a ‘Romper Room-type thing,” he said, referring to a children’s TV show that ran from 1953 til the mid-1990s.

(A spokeswoman for Franklin Covey did not respond to a request for comment from NBC News. The company received $2,824,816 in federal contracts in 2012, including $238,336 from the VA, according to the fedspending.org database.)

"If you don’t take it all the way down to where the results are actually achieved, then what you have is a wish list.”

John Mercer, a performance management consultant who helped ignite the drive for performance-based budgeting and management in the federal government, said that based on his recent conversations with staffers at the VA, it is clear that senior officials received little or no reliable data on how Shinseki’s goal was being acted on by front-line employees.

“This is a systemic problem throughout the federal government,” said Mercer, who drafted the Government Performance Results Act of 1993 -– the first attempt to introduce computerized, results-oriented management techniques at the federal level. “… If you don’t take it all the way down to where the results are actually achieved, then what you have is a wish list.”

In addition to lacking good data, some experts question whether wait time was an appropriate measurement for VA facility managers.

“The performance metric should not have been the waiting list but how existing resources were being utilized,” said Dr. Robert Roswell, who served as undersecretary of health in the VA from 2002 to 2004 and is now a professor of medicine at the University of Oklahoma. “A director can make sure that no-show appointments are minimized but has no ability to control how many veterans are seeking care at his or her facility.”

But Ed Barrows, a partner with the consulting firm Cambridge Performance Partners, said the VA’s management culture was the biggest problem.

“If the 14-day goal gets a lot of attention by management, it becomes a Dilbert cartoon, unfortunately,” said Barrows, who has consulted with the U.S. Commerce Department and the Navy. “… It’s not wrong to measure how many people are outside the 14-day window, but the nature of the culture, the way it cascaded down, the way leadership executed it created the opposite effect.”

Mercer, who served as a city councilman and mayor in Sunnyvale, Calif., before bringing his accountability ideas to Washington, said he and other city officials received plenty of data that allowed for accurate decision making. They knew, for example, how much it cost for a parks employee to mow an acre of grass, or a receptionist to handle a walk-in complaint from a constituent.

That hasn’t happened at the federal level, he said, despite a standard issued by the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board that took effect in 1995, which requires agencies to document the costs of providing basic services.

"Pretty soon you see something’s wrong. The numbers don’t match.”

If VA leaders had such data, said Mercer, they likely could have spotted anomalies in the Phoenix medical center’s appointment backlog.

“Then you can say, ‘Hey they’re doing really well in Phoenix. … let’s see how they’re doing it,’ said Mercer, now a senior consultant at Capital Novus of Fairfax, Va., who is trying to sell the VA and other federal agencies on software designed to ensure that performance goals and metrics flow through an entire organization. “And then pretty soon you see something’s wrong. The numbers don’t match.”

Such reporting gaps continue to exist despite multiple efforts over more than two decades to improve efficiency and accountability in federal government.

Following the Government Performance Results Act, signed in 1993 by former President Bill Clinton, former President George W. Bush added his imprint with the President’s Management Agenda in 2001 and the Program Assessment Rating Tool (PART).

The latest effort to improve efficiency is known as GEAR, for Goals-Engagement-Accountability-Results. Overseen by the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM), the fledgling effort encourages agencies to meet benchmarks for high quality performance appraisal systems. It is currently being tested at five federal agencies, including the VA’s National Cemetery Administration.

The use of the word “encourages” to describe GEAR highlights another problem with efforts to increase accountability in federal agencies, said Rubin.

“The Office of Performance Management establishes the basic requirements, but these are very broad and the agencies have a lot of flexibility as to how they design the systems,” she said, adding that the General Accounting Office and Office of Management and Budget also have some oversight of performance management, but “they can’t force agencies to make changes to their appraisal systems.”

In a statement to NBC News, a spokesperson for the OPM said that the VA’s performance management and appraisal system met its guidelines:

“The U.S. Office of Personnel Management’s approval of each agency’s performance management system is approval on the system design and the adherence of the system to OPM requirements …. The approval authorizes an agency to implement the system; however, the approval does not pertain to the actual application/operation of the system by the individual agency.”

The GAO and OMB declined to comment.

While the VA needs to revamp its system of monitoring workflow and rewarding standout performers, Rubin warned that any solution should not overload doctors and schedulers.

“What would you rather VA doctors and nurses were doing, treating patients or documenting everything?” she said. “We have to be careful that we don’t put so many constraints on them that it gets in the way of their serving veterans.”